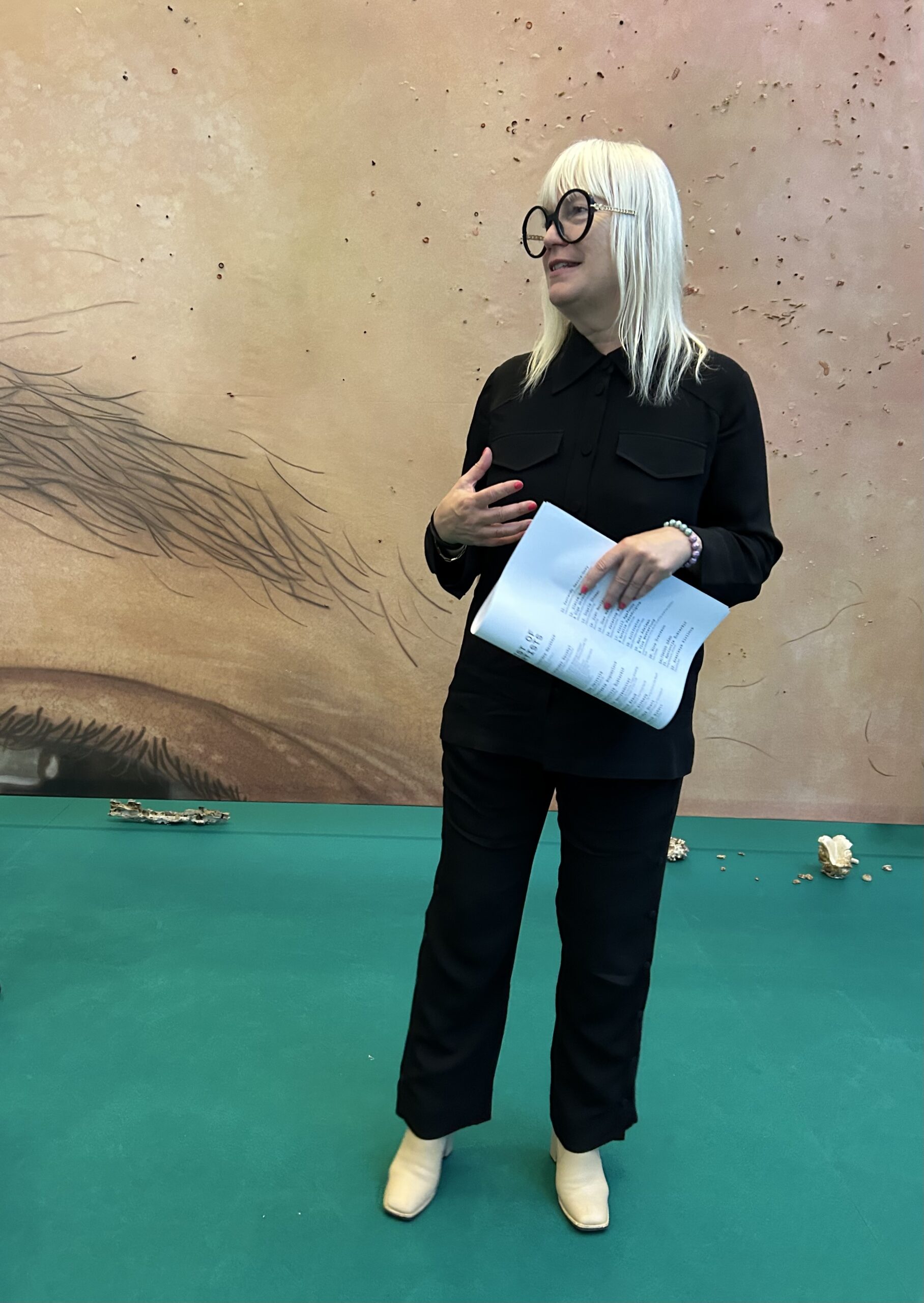

Swedish curator Maria Lind holds together a cultural core as Russia’s authoritarian upheaval tears at the fabric of Ukrainian society and grinds down the post-Soviet gains of Russian artists and cultural workers. By Steuart Wright

Traces of post-Soviet life are ubiquitous in The Observatory: Art and Life in the Critical Zone, an exhibition curated by Maria Lind when she was Sweden’s Counsellor for Cultural Affairs in Moscow in the months leading up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Her role was revealing of the organism that coalesces through curatorial work. A planned artistic exchange to be exhibited at the state art museum in Izhevsk in central Russia was transformed by the shock of the invasion into a series of engagements drawing on a global network that carried with it, and among others, visiting and self-exiled Russian artists and researchers, Ukrainian refugees, Swedish artists, a municipal art space, a museum and sanctuaries in the form of artist residencies. As geologists examine the accretion of geological material where a tectonic plate slides under the continental crust, The Observatory, which opened in Södertälje konsthall in September 2023 and Kin Museum of Contemporary Art in February 2024, brought into focus the transforming existential and ecological composition of a cultural accretion from this critical zone.

Ecologists designate the critical zone as the boundary layer between Earth and its near-surface atmosphere, from bedrock to the heights of forest canopies, a zone where earth, water, air, and living organisms interact in the transformation of Earth’s surface. It is the basis of a North American research network of critical-zone observatories, and it is no surprise cultural workers draw on it for inspiration to address emergent environmental and cultural phenomena as occupiers of this space. In her exhibition text, Lind explains that The Observatory “brings together a collection of new and existing artworks by twenty-six artists who, in diverse ways, actively engage in the critical zone … the art works reflect an array of phenomena, but also do things themselves, they actively perform.”

It was under a new regime of Russian censorship and economic and cultural sanctions that the moving of The Observatory from Izhevsk to Södertälje, Sweden, brought with it an added sense of urgency to the works of Russian and Ukrainian participants who otherwise may never have come to the southerly municipality of greater Stockholm. It was palpable in Alexander Ravskyi’s prints of digitally rendered line art of Ukrainian city buildings destroyed by the Russian attack and in his partner Alexandra Ravskaya’s tempera paintings titled: Air Raid Warning, Explosions at the Oil Plant, Air Defence System and Video Call. The Odessa couple were among more than 55 000 refugees that arrived in Sweden since March 2023. More subtly, Russian Olga Shirokostup’s healing decolonial research, Women in the North (working title), into the histories of displaced Soviet-era indigenous women and their environments, took on new meaning as Russian tanks carved fresh swathes of destruction into invaded Ukrainian territories to the southwest. Six million people had been forced to relocate by the end of 2023.

Small of stature with an energetic and sophisticated style, Shirokostup arrived in a claggy February amid the muted tones of winter on the Baltic island of Öland. I was her host at The Mirror Institution artist residency. Conversation through layers in trying to express what the war meant was made more difficult by the limitations of meeting through unfamiliar languages, but she had an authentic aspiration to connect at a human level, the common substrate from which we could explore the human, cultural and intellectual space around us. I had noted I was less than 2 000km from the front and a few hundred kilometres from the Nord Stream natural gas pipeline that was sabotaged, technical details that could not prepare me for what I was to become, an observer and a particle in a human sea experiencing waves from a far-off shock that would march onward, surely to inform such matters as artistic processes beyond my lifetime.

I encountered several more Russian artists and researchers through The Mirror’s connection to Lind who called on two residencies on the island to host visitors. Faced with re-evaluating what was meant by “home”, some would choose to return and others to continue an outbound journey deeper into Europe and beyond. Shirokostup would choose to return home, for now.

Lind took her post in Russia in August 2020. “I arrived at a time when it was an authoritarian state where things were getting tougher in terms of questions connected to LGBTQ and so-called foreign agents, legislation that was instigated in 2012 (restricting foreigners from establishing or participating in non-governmental organisations). My first day in the office at the embassy was the same day as the opposition leader Alexei Navalny was poisoned on an airplane above Siberia, so I certainly felt then that this was not going to be easy,” she explained.

Guided by her own curatorial lodestar, Lind prefers the term “working curatorially” to “curating” and she saw the role of promoting Swedish culture in Russia connected to exchange between cultural practitioners in person and online and by transmission of ideas through the people and institutions where she continues to cultivate engagement. So, the event of full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022, and Sweden’s official boycott of collaboration with Russian state institutions was more a shift in conditions and urgency around her practice than the emergence of a new role.

Lind explained: “Immediately after February 24 I decided to activate the networks that had been created since I arrived in August 2020. For every project I tried to connect it to webinars and to seminars, so prior to, for example the opening of an exhibition, people had at least met online. After February 24 we could meet on Zoom just to debrief about what was going on, what was happening in Russia, what people were saying outside the country. We had so many Zoom coffees in March, April, and May of that year and it worked because participants had already met, there was already a contact surface, and importantly, a concern. These gatherings were very emotional, with discussions, tears and laughter. I think this was meaningful and at the end of March we also started a webinar series called Despite: on the making of art under hardship in collaboration with two independent art schools, Moscow Institute of Contemporary Art and School of Engaged Art in St Petersburg. I just called my friends outside Russia asking: ‘Could you please talk about something connected to making art under hardship, it’s pro bono as I don’t have a budget, it’s very important right now especially for people inside Russia to understand that you can still make meaningful things.’”

When her contract ended in June 2023, Lind left Russia but continued spinning a curatorial thread from the engagements of The Observatoryparticipants by calling on Södertälje konsthall to host the exhibition before moving it to Kin Museum of Contemporary Art in northern Sweden, her new curatorial home as incumbent director. Lind cut her curatorial teeth in the 1990s and represents a school whose process evolved simultaneous to the emergence of contemporary curating as an academic subject. It is a brand of activism, informed by the maturing of feminism in her time, which has an eye for contemporary relevance, process in addition to object, and quality held to a standard of peer review and not audience numbers. It is a process that both enabled and derived material from continued support for cultural practitioners seeking new roles outside of Russia as well as those trying to function under its increasingly oppressive regime.

Younger than Lind, Shirokostup is an academic and carries forth many of her ideals. She is inspirational, highly productive and what drives her multi-disciplinary practice is difficult to grasp head on and better understood through conversations with her peers and through her works as a video artist, vocalist, performer, researcher, curator and educator. As her host, I hope she found solace after quitting her curatorial post amid an atmosphere of war-time national propaganda and restrictions on free expression.

I was amazed by Shirokostup’s sensitivity to the effects of the recurring seismic cultural disturbance that is Russia and her capacity to cultivate and guide understanding among those she encounters. Born in the north, but not of the north, she has found friendships in indigenous women displaced from their ancestral land to make way for the likes of her parents who sought the promise of new life in Soviet-era Murmansk, of Severmorsk – Russia’s administrative base of the northern naval fleet. She is driven by an urgent and humorous curiosity to reconcile her identity with her proximity to her female contemporaries with whom she shares an embodied reverence for the environment. She has also busied herself in bringing contemporary art from the country’s cultural centres to her peripheral homeland and given it expression in the active engagement of local citizens.

Independent researcher Christina Pestova arrived at The Mirror from Moscow via Germany and Denmark. Armed with a degree in literature, she has a quick intellect and a gentle curiosity which moves slowly in divining meaning from her surroundings as one might carefully examine a pool of water so as not to disturb the mud below. She was generous and sensitive in conversation which situated the current exodus of Russian intellectuals in relation to an ongoing post-Soviet post-colonial saga, an enriching juxtaposition to the predominant view of decolonial practice in relation to the Global South. Pestova is of kulak lineage, peasant farmers who were dislocated and dispossessed of their small farms as part of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s rolling purges. It appeared to me that at the heart of her stay was a very personal and creative quest looking to nature and the people around her to realign herself under a new constellation of relationships and territories. Of her time on the island, she wrote: “Dear Stu, I keep thinking about the experience of living in your house. I guess to many of us, the house became something bigger, greater than we expected. It is a pre-existing space with history and family in it, yet, at the same time, it is a space in transition. And, interestingly, this space is shaped together by so many people, the outlanders, coming to reside in it. I wrote to you about the theory that insects, birds and animals tend to get bigger on islands. I think I got bigger on Öland too. I hope one day I will be able to face my mainland.”

Christina continues her studies in Stockholm and Berlin. She was project co-ordinator for The Observatory.

Ulyana Podkorytova was not part of The Observatory but came to The Mirror, supported by the cultural department at the embassy of Sweden in Moscow, and revealed a process like Lind’s, in as much as it fit whatever she focused on, but it was an artistic practice making sense of life from an inner world out which made her insights fresh, personal and novel. With an intense curiosity, she explored the island on daily bicycle adventures and brought home reports from the architectural, agricultural, natural and atmospheric surroundings she encountered. Öland is widely known for being windy and before she left, she crafted a huge wind sculpture from disused military parachutes.

I found it complicated to express my sense of gratitude for the circumstance that brought me into contact with Shirokostup, Pestova and Podkorytova, because war was at the centre of it. Through their work I began to see profound similarities to the stream of ideas I experience as a South African grappling with that country’s colonial past. Of British and Dutch descent but a child of Africa, the question: “Who am I?” raised more questions than answers. To meet Shirokostup, Pestova, Podkorytova and their work was to reaffirm the sense of curiosity and humour required to heal rifts within and between people who have had their identities distorted by structural discrimination and injustice, to witness humility and wisdom at play through cultural work.

The human drama of setting down roots and building a life dependent on an inner identity while moving through an uncertain outer world was the genesis of Embassy of Microterritories, a collection of artefacts highlighting the existential journey of the young duo Kiril Agafonov and Natalia Peredvigina who also participated in The Observatory. The name of the place of their birth, in 1986, is listed in their passports but no longer exists. For two-and-a-half years Izhevsk was named Ustinov, after a Soviet Defence Minister, a place where military industry is the economic driver. They took Gorod Ustinov (city of Ustinov) as the name for their micro-art-group and its contemporary story. The artists’ collection, transported inside a 1980s “diplomat briefcase”, was packed and began the next leg of a journey as they fled Russia soon after the beginning of the full-scale invasion, fearing conscription and closed borders. The act deepened the work’s poignancy and emphasised how the artwork’s meaning shifted with time, space and events. Agafonov and Peredvigina also spent time on Öland as resident artists at Kultivator, an art and agriculture platform run by Malin Lindmark Vrijman and Mathieu Vrijman, long-time collaborators of Lind and co-exhibitors in The Observatory.

Agafonov explains the work: “It is important to make something like a root system and make it circulate and connect to people in other cultures. Microterritories is a search for something which gives a feeling of ground under our feet. It is a very existential quest, we started without an art education, there were no art institutions in the city. There were a few artists, but we wouldn’t call it exactly contemporary, so Microterritories was a search toward something which resonated and gave a possibility to catch or stand on in our own existence. Making this gives me feedback, if you like, of sewing something or cutting something, maybe showing it to people and it attracts some interest, this supports our existence. That is why we started to call it Microterritories, because it gives this support.”

Agafonovand Peredvigina are now based in Switzerland.

Through Lind’s motivation The Mirror had become participant and observer in The Observatory. On the transformation of art in Moscow, where her position stands vacant now, she said: “What you can see in culture, in public, at museums, cinemas, theatres, and so on, is all Russian – it’s either harmless or patriotic. Of course, people make interesting work, but they do it behind closed doors, it’s shown in more discrete circumstances, more underground. I also noticed that people have started to use metaphors, allegories and fables more, like they have historically in Russia and the Soviet Union. Every city and town I visited had an interesting thematic bookshop selling fiction, critical theory, philosophy, sociology etc. And they are much more than just book sellers – they are meeting places. In many of them you can sit and work, you can have a coffee, they have lecture series and so on. In Vladivostok, as far east as you can get, for example, one bookshop there is run by a philosophy professor from the university. He is even doing some of his teaching at the bookshop. This certainly gives him a different space to manoeuvre in terms of what he can say. The bookshops are somehow protected as commercial entities, at least for now, as NGOs they would have been shut down.”

Since heading up The Mirror with my wife Joanna Sandell Wright, I have contemplated themes that recur in art peculiar to different cultures. I found myself observing a familiar mode of none-left-behind humanity in the Russian residents and their artistic expressions that felt like home in relation to the vital artistic-intellectual project that is post-Apartheid South Africa. It is as if we shared a common ancestor, could it be a lack of humane and functional institutions in a post-liberation, post-hope era? Through working curatorially, Lind developed a rapid response network of independent operators and something of a platform which gave impetus to the dreams and motivations of participants as activists and observers trying to make sense of a critical historic disturbance.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.